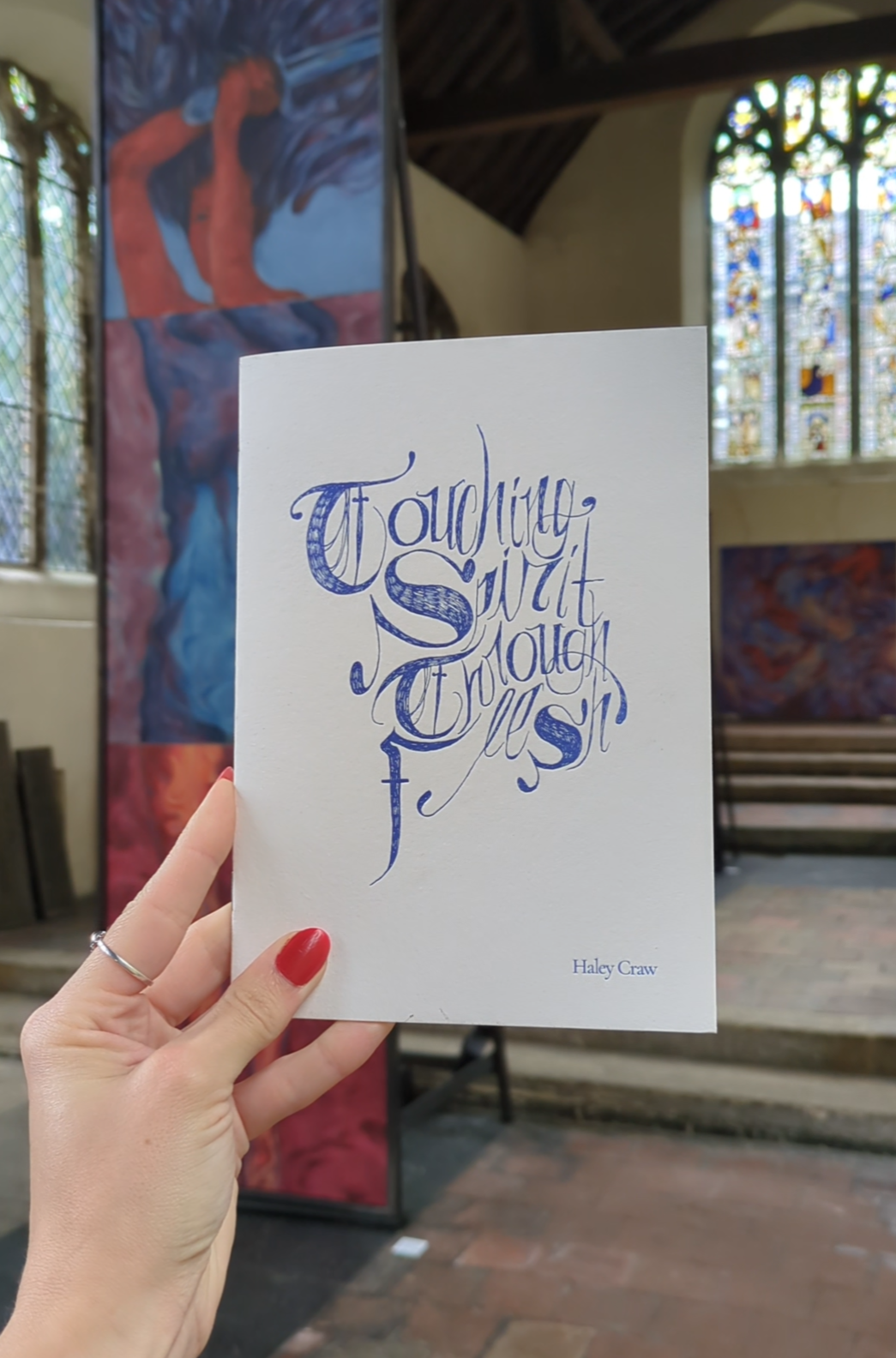

Touching Spirit Through Flesh Exhibition Text

Touching Spirit Through Flesh exhibition view, Hungate Medieval Art, 2025.

In the solo exhibition Touching Spirit Through Flesh, Haley Craw follows the voices and visions of medieval women, portraying the transforming emblems of an unseen world through a deeply intuitive creative process. Hiding in crevices, masses of hair, and on the wings of divine or diabolical creatures, the work explores the permeable boundaries of the flesh and the spirit. Two mystics from Norfolk are present spectres in Craw’s work, Julian of Norwich (c.1343-1416) and Margery Kempe (1373-1438), their mysticism rooted in a search for spiritual depth and meaning experienced through the body. As Simon Critchley describes, ‘Mysticism is about the spiritualization of the flesh and the fleshly, incarnate nature of the spirit’ (Critchley, 88), this is reflected in the vivid visions of Julian of Norwich layered in colourful sensation, and how Margery Kempe famously wept uncontrollably, her body physically releasing her internal passion. They present a ‘set of experiences that have allowed an author to move beyond the limits of normal human thought, into an area that is inexplicable and based on feelings or sensations. For mystical writers, knowledge - the preserve of the few - was not academic, but experiential’ (Ramirez, 7). This approach to seeking knowledge guided by sensation mirrors Craw’s creative process, using intuitive gesture, colour and form to depict vibrating figures that move beyond the barrier of skin and into an unfolding space within the ghostly imagination. The paintings merge personal expression with historical reference, depicting shape-shifting beings that challenge the border between the internal and external, who demand their presence be felt in a paradoxical realm they refuse to fully define.

Julian of Norwich (circa 1342-1416) was an anchoress in Norwich, this required the metaphorical death of her mortal flesh and her dedication to a spiritual existence in a secluded cell. In 1373 at the age 30, Julian experienced a set of intensely vivid visions over twelve hours following a nearly fatal illness. She spent the rest of her life considering the meaning of these visions, and wrote the book Revelations of Divine Love, the first book that we know with certainty was written by a woman in the English language. Julian expresses the human experience of weal and woe, of the burning pain we experience and the immolating fires of pure love, both death and life experienced in a single passionate moment. ‘What is a logical impossibility becomes possible in ritual, can find expression in the lived intensity of Julian’s devotional practice. What is opposed coincides performatively in the circling movement of Julian’s text, in ritual practice and in the enigmatic, shifting fabric of existence itself’ (Critchley, 174), complex connections to the natural world and the internal world circle within Julian, mirrored in the shifting motion of Craw’s paintings. Natural fragmented forms point towards figures that refuse to remain still and defined by a single shade, they accept contradiction as closer to reality than not, and look to what is beyond rather than in front.

All Mouth Becoming performance still, performed with Charlotte Arculus.

Julian of Norwich also emphasizes the maternal materiality of Christ, portraying the flesh of the Virgin Mary as one in the same as the substance of Christ, depicting a sensual, feminine body of the spirit. Julian blurs the bodily substances of blood and milk, describing how ‘the mother may lay the child tenderly to her breast, but our tender Mother, Jesus, he may homely lead us into his blessed breast, by his sweet open side, and shew therein part of the Godhead and the joys of Heaven, with ghostly sureness of endless bliss’ (Julian of Norwich, 132). Sucking on the side wound becomes an erotic expression of ecstatic devotion, a creaturely desire to consume. The flesh and the spirit merge into one, there is no distinction between the blood that flows through our veins, the breast milk that nurtures, and the spirit that defines existential meaning and emotional balance. ‘For as the body is clad in cloth, and the flesh in the skin, and the bones in the flesh, and the heart in the trunk, so are we, soul and body, clad and enclosed in the goodness of God’ (Julian of Norwich), peeling back layers of flesh, she exposes the spirit raw and kind, gentle and bleeding, seeing and feeling beyond the limits of time.

Lapis Lazuli Teeth. Oil on canvas, 152x122cm, 2024.

This Creature Sings. Oil on canvas, 81x130cm, 2025.

Medieval artistic representations that engage with feelings of the strange and monstrous appear in Craw’s work, portraying bodies that seem to yearn beyond their physical constraints. Depictions of Mary Magdalene covered in long flowing hair are referenced in the work, stemming from tales of her alleged time spent as a hermit in a cave in the south of France, with abundant hair serving as a form of divine modesty. Despite the modesty it is meant to serve, this hairy depiction conjures up a sense of unruly femininity, as Marina Warner describes ‘hairiness indicates animal nature: it is the distinctive sign of the wilderness and its inhabitants, and bears the freight of Judaeo-Christian ambivalence about the place of instinct and nature, fertility and sexuality’ (Warner, 359). The monstrous feminine defies ideas of pure and contained femininity, her closeness to her animal form and confident sensuality threatens patriarchal structures that position women as passive and weak. Medieval belief portrayed women as easily seduced and more likely to be the seducer, positioning them as both weak to temptation and a threat to male piety, both Eve and Lilith at the same time. Animals reoccur in Craw’s work to free women of this caged perspective, connecting women’s spiritual lives to the natural world, where hybrids and familiars roam. Julian of Norwich is often depicted with the one companion who shared her cell as an anchoress, a cat. Cat’s are historically connected to female sexuality, having strong associations as witches familiars, and ‘visionary activity was only one step removed from sorcery… Allegations of witchcraft arose out of ideas about the kinds of incorrect communications women were likely to have with the divine and the diabolical’ (Bale, 192). The imagination of women is seen as wild and uncontrollable, expressed through the skin and hair, her mind and body pose a threat to godliness. Creating images with a mysteriously sacred nature, the mind and body merge in Craw’s paintings, filled with abundant hair, sensual cave-like crevices, and transforming creatures praising their wild giantess.

Protective Spell II. Oil on canvas, 100x127cm, 2024.

Comparing the experience of isolated spiritual reflection in a cell or cave to that of the artist in the studio, reflecting inwardly and creating outwards, the internal vision is given a physical form in painting. From women such as Julian of Norwich living as an anchoress in her cell to tales of Mary Magdalene as a hermit in a cave, Craw’s work explores the romantic idea of a deeply felt internal search for meaning. Referencing Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own (1929), the importance of claiming personal creative space has a feminist dimension when space, privacy and intellectual freedom has not been historically afforded to women. Emboldening the creative lives of women is a means to claim autonomy and intellectual freedom. Woolf speaks to how the voices of women have been historically suppressed, ‘when, however, one reads of a witch being ducked, of a woman possessed by devils, of a wise woman selling herbs, or even of a remarkable man who had a mother, then I think we are on the track of a lost novelist, a suppressed poet…’ (Woolf, 48). At the time of Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe it was heretical for women to preach, and ‘given the mystical nature of her visions, her openly unconventional behaviour and her habit of preaching on her travels, Margery was in danger of being burnt as a heretic’ (Ramirez, 21). Their expression was carefully monitored so as not to overstep into diabolical forces, a divine messenger could easily become accused of heresy, and later witchcraft, by acting in any way outside of the strict parameters of acceptable behaviour expected of women. Even though they expressed themselves within the parameters of religion, they still verged on heresy due to the original sin of their bodies, ‘it is, therefore, important to remember that mystical thought, especially women’s visions which appeared to be unlicensed by male authority, could be met with rapturous approval but also with violent and deadly denunciation’ (Bale, 192). Joan of Arc and Marguerite Porete are two such examples of women with divine intention publically deemed heretic, both burned at the stake for the threat to order their voices posed. It is our legacy that a woman with an overactive imagination is always considered dangerous.

Returning Her Eyes. Oil on canvas, 40×122cm, steel, satin, 2025.

Dancing With Creatures Both Divine and Diabolical. Oil on canvas, 161x161cm, 2025.

The ability to hold up a mirror to the past, to find a voice that cuts through, provides space for those who follow for centuries to come. As Virginia Woolf states, ‘if you consider a great figure of the past, like Sappho, like the Lady Murasaki, like Emily Brontë, you will find that she is an inheritor as well as an originator, and has come into existence because women have come to have the habit of writing naturally’ (Woolf, 105). The past is always alive in the present, and creative freedom is made possible because of the groundwork of this legacy. The female figures in Craw’s work assert their gaze, body and spirit, they are strong and unflinching, taking up space as a giantess who has lived for centuries. The gaze is female, turning towards herself, the body asserts itself as in control rather than easily consumed. She reclaims the gaze by exposing the spirit raw and kind, gentle and bleeding with a sword in hand, a giantess who has lived for centuries. The paintings seek to reflect the women whose bodies filled these spaces for centuries, who dreamt, wept, feared and loved so passionately that the walls still contain their longing to be present. By looking at the women of the past who dared to speak when they were silenced, who dreamt of a larger life than they were allowed to lead, we can still feel the passion of a woman lost in her thoughts contained in these walls.

A Mirror for Simple and Annihilated Souls. Oil on canvas, 120×100cm, 2025.

Visions of Us in the Walls. Oil on canvas, 152x122cm, 2025.

Sources

Critchley, Simon. On Mysticism: The Experience of Ecstasy. Profile Books, 2024.

Edited by Eleanor Jackson & Julian Harrison. Medieval Women Voices & Visions. The British Library, 2024.

Julian of Norwich. Revelations of Divine Love. Edited by Dom Roger Hudleston, foreward by Kaya Oakes, Ixia Press, 2019.

Ramirez, Janina. Julian of Norwich: A Very Brief History. London, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2016.

Ramirez, Janina. Femina: A New History of the Middle Ages, Through the Women Written Out of It. London, WH Allen, 2022.

Warner, Marina. From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers. London, Chatto & Windus Ltd, 1994.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. London, The Hogarth Press, 1929.

This exhibition text was included in the limited release publication Touching Spirit Through Flesh which accompanied the exhibition. Printed by Rizzo Studio in Norwich, letterpress and risograph printed.